Method

Philology

In the Renaissance, science was freed from old tradition, and set out to discover how the world really worked. The success of the physical sciences is evident, and continues to this day. The humanistic sciences, which are chiefly the tex-based sciences, also started bravely, but soon ran into opposition from those who regarded those texts with religious veneration, or in the case of Homer and classical China, with a kindred cultural respect. Progress in these areas has thus been minimal. The cure is regular use of the classical methods of text study, which have no generally agreed name, but which we here call "philology."

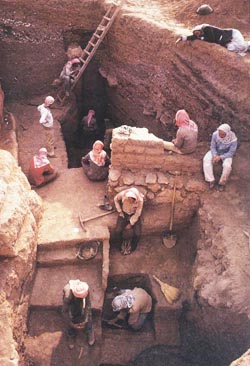

If you want to find Troy, you dig at Hissarlik, and several layers down, there it is. If you want to find Homer, you do as the earliest critics of Homer did - you identify intrusions and extensions, and underneath them all, there is the original text. Considering the original together with its extensions and additions, we can appreciate the way it grew. We can get a sense of the opportunities and oppositions it encountered during its active lifetime. That is, we can read the text - the original and the extensions together - as history. We can recover that part of the past, not in general, but in detail, "as it really happened." And what really happened will not be a picture, but a process.

The one constant fact about history is that it changes

The most important thing about ancient texts is that they also change, to keep up with the changing timesPreliminary. If a text exists in several manuscripts, they must be compared, and their differences - scribal mistakes or improvements - must be identified. This is called the Lower Criticism. It is well understood, and need not detain us here. What comes next is the

The Higher Criticism uses the evidence in the text itself to recover any earlier history. Specifically, the higher criticism seeks to identify additions in one text, and to assess directionality between two related passages:

Extensions. The commonest places to accommodate growth are at the end of the previous test; less commonly, at the beginning. Examples of such extension can be recognized in the texts of most antiquities. For an overview of such examples, see the Text Formation Primer.

Interpolations. The text proprietors (such as the leaders of a philosophical school) may also add material within the text, to correct or explain an existing passage. Interpolations may break a previous formal pattern (in the Analects of Confucius, they often interrupt an original pair of sayings), or are otherwise discordant with their surroundings. If a suspected passage is removed, and the surrounding text closes up like your finger when you take a splinter out, then that was an interpolation. For this and the preceding, see our Text Formation Primer.

Forgeries must be identified. The usual method is the recognition of anachronisms, showing that the text could not have been written at the date it claims for itself. Famous recent examples are the Donation of Constantine (a forgery of the time of Charlemagne, exposed by Valla) and the Letters of Phalaris (a forgery of the time of Bentley, exposed by Bentley).

Directionality. Passages in different texts may be related. One may echo another, or correct another along doctrinal lines. In China, Sywndz and Mencius argue over human nature. The Analects responds with spirit to some anti-Confucian satires in the Jwangdz. The statecraft texts labor to discover the ideal form of the new state that was emerging in the classical period; other texts deplore the new state as such. The military texts show how to win at the new kind of warfare, later ones improve on the earlier ones, and opposition texts deplore all warfare. At the other end of the ancient Asian trade route, Nahum exults over the destruction of Nineveh; Jonah satirizes the whole business of prophesying doom. Ezra deplores foreign wives as defiling, and demands that they be divorced; Ruth slyly reminds everyone that ancestors of the honored King David included a mixed marriage. Such contacts between texts must be identified, and their directionality ascertained. Only then does the nature, not of the individual texts, but of the corpus of texts, and the culture in which that corpus of texts took shape, become clear.

Chronology. From many directionality determinations, we can gradually build up a relative chronology: a system of interrelated texts, perhaps anchored at some points to specific years. At that point, we begin to be in possession of the wider historical past, and can watch the whole thing grow.

Style One helpful addition to those ancient tools is a test of stylistic difference called BIRD, which can assist in identifying intrusive material (whether as extensions or interpolations), or in verifying that passages in different texts are closely related; see the Style section. The first public presentation of that test, combined with an extended example of traditional philology, was at Leiden in September 2003.

Here are links to that and to other presentations illustrating the basic techniques of philology, in one antiquity or another:

- The Lower Criticism

- Housman on Textual Criticism (1921, abridged)

- A Text Formation Primer (2022)

- Intellectual Dynamics of the Warring States Period (1997)

- Alexandrian Motifs in Chinese Texts (1999)

- Mencius (Singapore 1999)

- Bactria

- Before and After Matthew (0000)

- Philology in an Old Key: Lord Shang Revisited (Leiden 2003)

- Heaven, Li, and the Formation of the Zuozhuan (2004)

- Works Cited

And as with many things that people do, some are better at this than others. For sketches of some who have contributed notably to the untangling of ancient texts, in China or elsewhere, see our Gallery of Philologists.

All materials on this site are Copyright © 1993 or subsequently by the Warring States Project or by individual authors