History

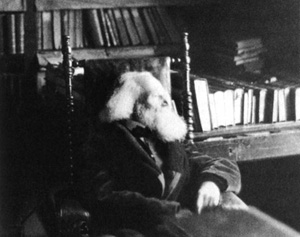

Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (Wiehe 12 December 1795 - Berlin 23 May 1886) did not invent the footnote, or the concept of primary sources. His archival researches were revolutionary in implication, but his own writings did not fully exemplify the ideal of "scientific" history. He supported the Prussian state more than a modern liberal might have done (he was appointed Royal Historiographer by Friedrich Wilhelm IV in 1841, and ennobled by Wilhelm I in 1865, whence the "von" in his name). But he was a cosmopolitan (he had met his Irish wife Clarissa in Paris; their home in Berlin was a social focus for Shakespeare readings as well as Goethe conversations). He believed in God, always a temptation to a historian, though he rejected the misty teleology of Hegel (at Berlin, he and Hegel defined the two principal opposing factions among the faculty). And he ignored other schematisms, confident that any larger movements would emerge from careful study of the details.

Neither he nor his disciples (not Mommsen, not Burkhardt, not Meinicke, not even Ludwig Riess, who carried the ideal of the new history to Japan) left a textbook of method. Ranke, like Confucius, taught by aphorism. Here are some of the chief aphorisms (to see the German originals, click on these English versions). Would longer ones really tell us more?

"But it is not for the past as a part of the present, but for the past as the past, that man is properly concerned" (Diaries, 1814)

"History has had assigned to it the office of judging the past and of instructing the present for the benefit of future ages. To such high offices the present work does not presume; it seeks only to show the past as it really was" (History of the Latin and German Peoples, 1824)

"I would maintain, on the contrary, that every epoch is immediate to God, and that its value in no way depends on what may have eventuated from it, but rather in its existence alone, its own unique particularity" (Lectures to King Maximilian of Bavaria, 1854)

"I see the time coming when we will base modern history no longer on secondhand reports, or even on contemporary historians, save where they had direct knowledge, and still less on works yet more distant from the period; but rather on eyewitness accounts and on the most genuine, the most immediate, sources" (History of Germany in the Reformation, 1839)

Here are a few further notes about Ranke and his idea of history:

- Portrait of Pope Paul IV (a sample of Ranke's historical writing style, 1834)

- The Unity of Truth (from the History of Germany in the Reformation, 1839)

- A Historian Must Be Old (Diaries, 1877)

Readings

- Theodore von Laue. Leopold von Ranke: The Formative Years. Princeton 1950

- Peter Gay. Style in History. Basic 1974. One chapter is devoted to Ranke

- Leonard Krieger. Ranke: The Meaning of History. Chicago 1977

- Roger Wines (ed). Leopold von Ranke: The Secret of World History. Selected Writings on the Art and Science of History. Fordham 1981. Extracts some theoretical pronouncements and examples, and includes the longest of Ranke's several autobiographical notes.

- Wolfgang J Mommsen (ed). Leopold von Ranke und die moderne Geschichtswissenschaft. (Stuttgart) Klert Cotta 1988

- James M Powell and Georg G Iggers. Leopold von Ranke and the Shaping of the Historical Discipline. Syracuse 1990

- John S Brownlee. Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600-1945. UBC 1997. Chapter 6 ("European Influences on Meiji Historical Writing") recounts the transplantation of the Rankean ideal.

- Georg G Iggers. Historiography in the Twentieth Century. Wesleyan 1997. A note on modern historiography's Rankean beginnings is at 24-26; see also the Index for a sense of his present position in the field.

- Kelly Boyd (ed). Encyclopedia of Historians and History Writing. Fitzroy Dearborn 1999. The article on Ranke (by Helen Liebel-Weckowicz) is at 2/981f

15 June 2004 / Contact The Project / Exit to Home Page