Errors

The Lisbon Earthquake

Disconnecting Events from IdeasThe Lisbon Earthquake Error is the belief that thought arises and exists in isolation from life.

One of the most dramatic examples of life influencing thought is the Lisbon Earthquake of 1755, which produced a disaster in Lisbon, did damage for hundreds of miles around, and sent a shock wave through the thought of all of Europe, both sacred and profane. We here briefly recapitulate the facts, and conclude with an extreme and recent example of the error.

What Happened

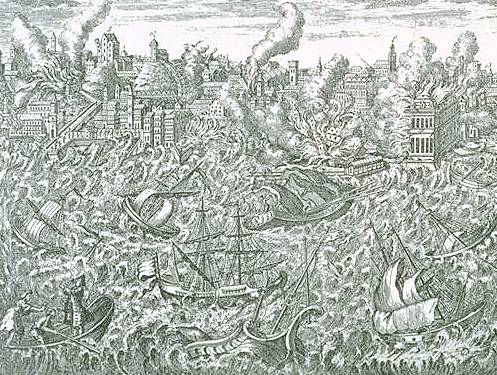

On All Saints' Day, 1 November 1755, about 9:30 in the morning, Lisbon felt the rumbling shock of an earthquake. After a brief pause, a devastating second shock, lasting two minutes, brought buildings down in a deafening roar of destruction. Shortly after this came a third shock causing further damage, and a cloud of dust settled like a fog over the city. Fires broke out, and became a general conflagration. Some people managed to escape to the waterfront. As they were embarking in flight from the ruined city, an hour after the earthquakes, the waters of the Tagus rose menacingly and poured in three great towering waves over its banks, breaking with tremendous impact on the Lisbon quays and foreshore. The harbor waters became unmanageable, and many small boats were lost. Here is a contemporary engraving:

Shocks were also felt, and considerable damage was done, at other places in Iberia and North Africa, southern France, Northern Italy, and Switzerland. The tsunami waves reached England by 2 PM, and the West Indies by 6 PM that evening, and waters were disturbed as far away as Scandinavia. But Lisbon bore the brunt. Much of the city was destroyed, and by sober modern estimates not less than 15,000 people lost their lives. Rumor at the time made the toll 30,000 or 60,000.

What Followed

The second shock was to European opinion. Theologists struggled to justify this obvious act of God as an intention of God, and to explain what guilt Lisbon's inhabitants had cumulatively incurred to merit such dramatic retribution. Further disasters were prophesied. This produced terror in the lower populace, and derision among the learned. But the learned too were affected. The 18th century had been a period of philosophical optimism. The discoveries of Newton and Leibniz promised rational explanations of the order of nature, somehow in harmony with the designs of God. Voltaire, the typical figure of the age and of the learned Reaction, had been deeply impressed by Newton while visiting in England, and continued to be an admirer of Leibniz after his return to France. It seemed to him that the mind of man, aided in his case by a deistic sense of a general and benign Providence, had taken the measure of the cosmos.

In all this he was suddenly undeceived. His entry into pessimism was made with a Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne, printed in censored form in 1756 and immediately arousing controversy, including a sharp correspondence with the young Rousseau, who found it blasphemous and unacceptable. A certain Louis de Beausobre defended the tout est bien school of thought in a book called Essai sur le Bonheur (1758). He did his best to reason away the earthquake. Men die, but men always die. God remains good.

Voltaire returned to the attack in 1759 with his viciously satirical novel Candide, in which the naive hero is instructed by his tutor Pangloss (representing the clerics of the age) as to why various unoffending persons deserved to die in a particularly sudden and horrible way. Here is the scene as Candide and Pangloss are approaching the harbor of Lisbon, among the passengers being an Anabaptist who had befriended Candide earlier in his travels:

Half of the passengers, exhausted and violently seasick, were too miserable even to worry about their danger; but the others kept crying out in terror and praying. The sails were torn; the masts broke; the ship began to leak very badly. Those who could tried to keep her under control, but nobody know what ought to be done and nobody gave any orders. The Anabaptist was trying to help on deck when a brutal sailor struck him hard and sent him sprawling, so hard that on the recoil the wretch fell overboard headfirst and hung over the waters hooked up on a bit of broken mast. The kindly Anabaptist picked himself up and tried to rescue him, but in the effort of doing so he was himself thrown into the sea and was drowned in full view of the man he had saved, who let him perish without even giving him a look. Candide came up at this moment and saw his poor benefactor appear for the last time and then disappear forever. He wanted to throw himself off into the sea after him, but Pangloss stopped him, pointing out that the Tagus approach to Lisbon had been created on purpose for this Anabaptist to be drowned in it . . .Voltaire's novel was published, and, as Kendrick puts it, "the whole tout est bien philosophy was thereby blown to pieces in company with poor Louis de Beausobre's book and everything else of the kind, to the accompaniment of the derisive laughter of literary Europe."

Take what side you like on the question of Leibniz's theodicy, and that side was vigorously argued. In public, at the time and for decades thereafter. Lisbon changed the map of 18th century thought.

The Error in Action

The memory of the Lisbon Earthquake has not been forgotten among historians of philosophy. Rather, it has been suppressed. In the Routledge Concise Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2001), we have this epitome of the thought of Voltaire:

After his stay in England, Voltaire became interested in philosophical optimism, and his thinking reflected closely Newton's view of a divinely ordered human condition . . . This was reinforced for the young Voltaire by Leibnizian optimism, which offered the view that the material world, being necessarily the perfect creation of an omnipotent and beneficent God, was the "best of all possible worlds," that is to say the form of creation chosen by God as being that in which the optimum amount of good could be enjoyed at the cost of the least amount of evil.Voltaire's later dissatisfaction with optimistic theory brought with it a similar loss of faith in the notion of a meaningful order of nature, and his earlier acceptance of the reality of human freedom of decision-taking and action was replaced after 1748 with a growing conviction that such freedom was illusory. The 1750's witness Voltaire's final abandonment of optimism and providentialism in favour of a more deterministically orientated position in which a much bleaker view of human life and destiny predominates . . .

In this universe of explication, either thought has other thought as its cause, or it has nothing as its cause. What in the 1750's led Voltaire to abandon previously held views? This author does not feel required to say. Thought gives way to thought, untrammeled by anything outside the realm of thought.

The fallacy here illustrated is not confined to philosophy. The archaeologists have their version. So do many other corners of the academy. The general error is departmental. It is the mistaking of a toolkit for a discipline. If put into words, it would run like this: "What we [philosophers, or whatever] uniquely do is sufficient to answer all questions of concern to us; we do not allow the intrusion of other factors, such as a historian might handle." This is nonsense. A discipline, a toolkit, is a way of doing certain things; it is not an equipment for the whole of life. Familiarity with the technica of philosophy [or whatever] is a contribution to the understanding of history. It does not replace the understanding of history.

At least, not in the best of all possible worlds.

15 June 2004 / Contact The Project / Exit to Home Page