Seeing History

EvidenceEvidence is what you rely on for information about something you don't know directly. The perils of evidence are obvious, but there is no harm in quoting an early investigator:

What men inhabited Africa originally, and who came later, or how the races mingled, I shall tell as briefly as possible. Although my account varies from the prevailing tradition, I give it as it was translated to me from the Punic books said to have been written by King Hiempsal, and in accordance with what the dwellers in that land believe. But the responsibility for its truth will rest with my authorities. (Sallust, Jugurtha 17, tr Rolphe)

Notice the layers of doubt between Sallust and the facts: (1) the accuracy of the translation that was done for him, (2) the identity of the original author, and (3) the accuracy of that author's information. There is also (4) "what the dwellers in that land believe." In the nature of things, what a later age believes is liable to be self-congratulatory rather than merely factual; a past shaped to the needs of the present.

And we can put that back a step. The above quote from Sallust is Rolphe's translation from Sallust's Latin. How good a translation? As we use that translation, how close are we, really, to what Sallust said? Here is the Latin text from which Rolphe was working:

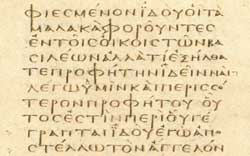

Sed qui mortales initio Africam habuerint, quique postea accesserint, aut quo modo inter se permixti sint, quamquam ab ea fama quae plerosque optinet divorsum est, tamen uti ex libris Punicis, qui regis Hiempsalis dicebantur, interpretatum nobis est, utique rem sese habere cultores eius terrae putant, quam paucissumis dicam. Ceterum fides eius rei penes auctores erit. (Sallust, Jugurtha 17)

And where did this Latin text itself come from? From a best compromise among the readings of various manuscript copies, none of them very close in time to Sallust. The art of putting together different late copies so as to get as near as possible to the state of the text from which they may have diverged is part of the equipment of the historian, or at any rate, it is somehow part of the job of history. Now you know why Rolphe spent the last four pages of his Introduction telling us about the age and location of the manuscripts he used. His Preface begins:

In the absence of an entirely satisfactory text of Sallust, the translator has made his own. In some points of orthography, for example in the assimilation of prepositions, he has not followed the manuscripts, but has aimed rather at uniformity.

Uniformity is good, especially if it is the uniformity of Sallust, but suppose the reconstructed text is instead not uniform? Suppose its nonuniformity represents differences, unhomogenized by Sallust, in the sources which he used? Here might be a clue to something we would like to know more about. No?

Some will say, No. They will lose patience. But the thing about doing history right is that it requires a lot of patience. The patience may be yours or it may be somebody else's (Rolphe would have used an existing critical text, if there had been a satisfactory one). But somebody has to do it. In the present age, after centuries of other people's careful labor in establishing the best texts of the Latin writers, we may find ourselves driving down a clear road, with a previously well edited text before us, and able to ignore such things as manuscript variants. But even on a clear road, you can have a flat tire: a seeming error in the editing. The well equipped historian is the one who can get out of the car and fix the flat.

Earlier Evidence

The basic fact about evidence is that late testimony has been longer exposed to the wishes of posterity than has early testimony. The default principle is thus that the earliest evidence is the best evidence. Rather than get it from the Britannica, get it from the documents on which the Britannica author relied. Ranke has defined this principle for modern historians in this way,

"I see the time coming when we will base modern history no longer on secondhand reports, or even on contemporary historians, save where they had direct knowledge, and still less on works yet more distant from the period; but rather on eyewitness accounts and on the most genuine, the most immediate, sources." (History of Germany in the Reformation, 1839)

The key is "direct knowledge." Nor does the problem end there, since a contemporary may be ill-informed, or disingenuous. As every lawyer knows, eyewitnesses are often fallible. But these are the problems of any evidence. If we eliminate other sources of difficulty, we will be better off than if we don't. Insofar as possible, we need to hear the testimony of the earlier period about itself. The earlier evidence is where we are most likely to get that testimony, and to get it with minimum dilution.

Situations where physically later evidence may be substantively earlier are merely a variant of the basic rule, not a refutation of it. My xerox of part of Codex Vaticanus was made in the year 1997. My family Bible is a King James Version printed in 1904. My family Bible is thus 93 years older than my copy of Vaticanus. But is it better? No. The Vaticanus facsimile directly preserves a 4th century text, whereas the King James translators relied on Greek manuscripts going back at earliest to the 6th century. My Vaticanus copy is thus, in effect, 2 centuries older than my Bible. Such exceptions need to be established by careful argument, case by case, but they raise no difficulties of principle.

Later Evidence

Later evidence is still evidence - but it is evidence for the later period. The Byzantine text of the New Testament (which is what we read in our King James versions) is the authoritative witness to the way the Byzantines wanted to present the scriptures: smoothed and unproblematic, and not requiring erudition in the reader. Similarly, a history of China written in the 04th century is a precious document for the mind of the 04th century: for how that age saw earlier ages, and for the lessons it wanted to find, or the precedents it wanted to insert, in those earlier ages; the enablements it wanted from antiquity. The only error is to treat that retrospective agenda as though it were a videotape of the earlier ages themselves.

We may add that resistance to the principle of earlier evidence is well developed in some fields. The findings of the New Testament text critics have been countered by arguments in favor of the Byzantine "received" text. (There are even people who argue that the King James Bible is correct because God spoke English). Chinese commentators sometimes defend the contents of chronologically later texts in a manner reminiscent of the Byzantine text partisans. Thus, it is common practice in contemporary Sinology:

- . . . to concede that a given text may be late, but then to assert that its content is more authentic than that of an admittedly early text,

- . . . to cite post-Han forms of myth as superior to, and thus as older than, the simpler forms of those myths contained in earlier texts,

- . . . to admit that texts may not derive from the persons conventionally associated with them, but to proceed anyway, as though they did so derive.

This situation does not change the rules of history, but it does complicate the playing field for those doing history. Tswei Shu in the 18th century (and Gu Jye-gang independently in the 20th century) discovered that the ancient Chinese emperor lore had been built up in reverse, with the later invented figures being added at the earliest end of the chronology. This reverse antiquity model has had a hard time making itself felt. The shouts of the antiquity fans tend to drown it out. It remains, however, a model and a caution for the objective historian.

The Rejection of Change

The ultimate denial of the value of earlier evidence is the denial that historical change takes place at all. This position, or a position that comes to the same thing, is not at all uncommon in our world.

Cultural continuity, social self-identify, can be emphasized by states and their apologists to the exclusion of all else. Historical religions have problems precisely with their historicity, which is always potentially at war with their claim to be valid for all times and places. Attempts to deal with that problem as it arises in Christianity can be seen already in the successive layers of the Synoptic Gospels, which present a progressively dehistoricized Jesus. From the Chinese version of the Antiquity Delusion, we see that historical ideologies have analogous problems. Confucius was mythologically transformed in the late Warring States and the early Empire, but in the end, not quite enough to pry him loose from his historical placement in the late 06th and early 05th centuries. He was then functionally replaced as a cultural authority by the classical texts which (it was wrongly claimed) he had edited. This substitution extended the authority of Confucianism far beyond Confucius, to the time of the supposed sage emperors of antiquity. It homogenized the history of the Chinese mind.

We need hardly add that the compilation date of most of the Chinese classics, and the date of most of the material which they contain, is well after the lifetime of Confucius. The best evidence for Confucius not only implies that he did not edit those texts, it implies that he did not even know of them. If we confine ourselves to the earliest evidence, it seems instead that Confucius taught from first principles and direct experience; see The Original Analects p19.

Earliest evidence is best evidence. It may take work to establish what evidence is the earliest. Well, then it does. That is the price of admission to the history part, rather than another part, of the human comedy.

Readings

- J C Rolphe. Sallust. [Loeb Classical Library]. Heinemann 1921

- A Taeko Brooks. Heaven, Li, and the Formation of the Zuozhuan. Oriens Extremus (2003-2004) 51-100. Locates the ethical and naturalistic theories of history as they developed, in turn, over the span of time in which this 04c accretional text was written and expanded.

- E Bruce Brooks and A Taeko Brooks. The Original Analects. Columbia 1998

17 Dec 2006 / Contact The Project / Exit to Outline Index Page