Sinological Profiles

Nancy Lee Swan

9 Feb 1881 (Tyler, Texas) - 15 May 1966 (El Paso, Texas)The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, volume 8 #4, still exists to inform us that at the meeting of 2 March 1905, there were elected to membership seventeen people including "Miss Nancy Lee Swann" of Tyler, Texas, then in her 24th year. Also presented at that meeting was a report showing that, as of the end of the previous month, the bank balance of the Association was $1,049.40, on deposit at the City National Bank with interest accruing at the rate of 4%. The Association, it is clear from that report, was upheld chiefly by membership dues ($620.45); sales of the Quarterly ($17.50) were a negligible factor in its solvency.

With this admirably precise fiscal note, we begin what was to become an economical tale of our times.

In the 1910s and 1920s, Guion Moore Gest (1864-1948), founder of the Gest Engineering Company, made frequent business visits to Peking, and having had a glaucoma condition relieved if not quite cured by a local remedy, charged his friend Commander I V Gillis (1875-1948) to collect Chinese books having to do with eye diseases. This mandate rapidly expanded to Chinese medicine, then to other sciences, and then to the classics and traditional Chinese learning at large. Gillis was a dangerous person to entrust with an open mandate. He was married to a Manchu princess, and thus had certain advantages of access to the Peking elite. The core of what eventually became the Gest Oriental Collection was obtained by Gillis from the tutor to the Sywaentung Emperor, with significant additions also from Jang Jr-dung, Li Hung-jang, Tsai Ywaen-pei,and Ywaen Tung-li. So successful was Gillis in his endeavors that he impoverished Gest, who in any case had no place to put the resulting pile of books. In 1926, it was arranged that the collection, then numbering 232 titles in 8,000 fascicles, would be housed at specially prepared quarters at McGill University in Montréal. By 1932, the collection would have grown to more than 100,000 volumes. Its subsequent history illustrates the awkward transition between a rarities collection and a working collection, one key difference being that a working collection requires the presence of someone other than its curator to work on it. In the first half of the 20th century in North America, which was something of a Sinological wilderness, that requirement was more easily stated than met.

The collection's first curator at McGill was one Robert de Résillac-Roese, whose Chinese was not adequate to the task, and of whose Chinese assistants' acquaintance with their native literature, the less said the better. Gillis's comment, when he received the resulting catalogue, was "truly pathetic." Nancy Lee Swann had joined the library in 1928, and brought greater competence to the task of redoing all the cataloguing.

The crash of 1929 eliminated whatever of Gest's money remained after Gillis's ambitious book buying. But though Gest was wiped out financially, his former library continued its own existence at Montréal. As well it might: Gillis continued to acquire books for it with $10,000 of his own funds, and Swann served as curator without any pay at all. The thing had a life of its own. It was bigger than all three of them.

In 1931, Swann's biography of a Latter Han empress, originally a 22-page article in JAOS, was published as the first in a McGill series of monographs on China. In that year officially, and presumably with a salary, she became Curator of the Gest Collection.

Also in that year, Swann received her PhD from Columbia. The following year, 1932, saw the publication of her thesis, a more ambitious study of Ban Jau, the sister of Ban Gu and the neglected third author of the Han Shu (Swann gives Ban Jau credit for about a fourth of the whole). This work was also published for a wider audience by the Century Company under the aegis of the American Historical Association.

A study of a rich female merchant from Ba, from the chapter of the Han Shu dealing with wealthy individuals (HS 91, paralleling SJ 129), appeared in JAOS in 1934. Swann was getting the range for what would become her major work. She noted at the beginning of her piece that these chapters

. . . have a peculiar interest not only to the economist, but also to the general student of Chinese Culture.

This credits the general student with a more broadly humane horizon of interest than later experience has tended to confirm, but all the same, it was the right note to strike. Meanwhile, perhaps no deep psychological analysis is necessary to understand why someone who had gone through the Depression with a salary sometimes amounting to zero would be interested in economics.

Swann notes that the few lines devoted to her woman merchant are appended to a previous entry in SJ 129, whereas in HS 91 they are separated as a paragraph of their own:

A few additional commentarial phrases, which are not included in the account found in the [Han Shu], are recorded about her in the [Shr Ji], but in the Han-shu her biography - perhaps due to the share of Pan Chao in the latter history - is set forth independently of that of the rich cattleman to whose biography in the Shih-chi her record forms a supplementary illustrative part.

Nicely observed. But as for the "commentarial phrases," which at the end of her article Swann describes as being "added to" the SJ version, it would be more consistent with that observation to think of them as deleted in the HS version. The reason they were deleted, by whoever separated the two SJ accounts, is that in SJ they are a joint summary of those two accounts, and if that summary were divided among the now separate entries, the two accounts would have ended with exactly the same words. Here was a missed opportunity to contribute to the still ongoing debate on whether SJ or HS chapters are primary, when parallel topics are treated in both works. Swann had a second chance at this issue when she included parallel translations of both chapters in her long-incubated Food and Money in Ancient China (silently incorporating whole paragraphs from her 1934 article). This second chance she explicitly declined:

No attempt has been made in this study to determine wither what material in the Shih-chi was originally there and just taken over by the historians in their work on the Han Shu, or what material originally included in the Han Shu was later interpolated into an incompleted Shih-chi.

On this point, at least, Swann's work was cumulative. She had delivered her final verdict in 1934.

Continuing money problems induced the Gest Collection to search for another home, but no Canadian or American institution was willing to take it on. Negotiations for transfer met with the firm McGill opinion that McGill owned the Library, and that was that. Finally, with support from the Rockefeller Institution for Medical Research (for which he had earlier organized a study on the merits of acupuncture), Gest was enabled to repurchase his library from McGill, and arrange for its removal to the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. This logistically complicated process began in 1936. Amidst it all, Swann contributed a serene and learned article on "Seven Intimate Library Owners" to HJAS. The Library move was completed in 1937. In its new home, it was something of an albatross. It was expensive to house and maintain. The Institute had no personnel competent in Chinese. Princeton University itself, at that time, did not yet have an academic department for the study of Chinese.

Swann moved to the Institute along with the Gest Library, and continued as Curator through the war years, doing much to expand the collection, and thus becoming, along with Gillis, one of its principal architects.

She also kept up a statesmanly posture, and was present at the momentous meeting of 9 June 1941, when the Association for Asian Studies was organized out of the ashes of the previous Far Eastern Association. With her at the meeting were Knight Biggerstaff, Woodbridge Bingham, Hugh Borton, Herrlee G Creel, Charles B Fahs, John K Fairbank, Clarence H Hamilton, William W Lockwood, Earl H Pritchard, Edwin O Reischauer, Laurence S C Sickman, and Joseph K Yamagiwa. Fast company.

In 1942 she was jointly in charge of membership recruitment in the New York City area, for the American Oriental Society. Her work on the Han economy surfaced in a paper, On Han Money According to the Treatise on Economics of the Han Shu, which was "read by title" at the American Oriental Society meeting of May 1942. In late 1944 she issued a review, by no means wholly laudatory, of the first two volumes of Dubs' translations from the Han Shu:

Errors in translation and inconsistent interpretations will unavoidably occur in a work of this scope. It is not a happy choice to render the tragic fact that people in times of famine did "eat other [people'," that is, human flesh, as "people eat each other" (i, 82 ff), or "people eat one another" (ii, 305).

Or to put it directly, the adverb syang is not necessarily reciprocal in meaning, a fact that students of classical Chinese whose first linguistic basis is in modern Chinese keep rediscovering, at some point or other, in their careers.

The job of being in charge of the library competed, in these years, with Swann's use of the library. But by early 1945, fourteen years out from her PhD thesis, Swann felt she had completed her masterpiece, Food and Money in Ancient China, a lavishly annotated translation of Han Shu 24 and certain parallel texts. The book was dedicated to Gest, who was then still living. An economist colleague, Robert B Warren, had come to the Institute in 1939 as part of an Institute move to include more practical people, had taken part in a 1941 symposium on Financing the War, and had gone on to advise the US Treasury for the duration of the war. He wrote an Introduction to Swann's book (dated 9 Feb 1945), in which he reminds the reader of the Ptolemaic Egyptian parallels, and lauds HS 24 as having

. . . no counterpart in western history, either in content or in design. It covers a long period of time, but it is not a comprehensive history, for it is confined to economic developments in a partially "planned" society.

The book itself was still five years away from issue. One chore that occupied Swann at about this time or a little earlier was the sending out of drafts to eminent economic historians for criticism. Swann thanks Yang Lien-sheng in her Introduction for his suggestions, so also Hu Shih and J J L Duyvendak, who "devoted much time both to making suggestions for improvements in the translations, and to pointing out errors of commission and of omission in the study as a whole." A copy sent to Duyvendak's student and eventual successor A F P Hulsewe fared not so well; he made a number of annotations on the typescript, but never returned it to Swann.

There were also economic problems of a strictly contemporary sort. In 1946, approaching the retirement age 65, Swann said in a letter to Gillis:

...This is my last year of service as active curator of the Library, but I rather hope that some plan can be worked out by which I can spend seven or eight months each year in Princeton, and enjoy working on my own without the responsibilities of the irritating little things that have been my lot to do in all these years since I have been connected with the Library. I have an idea that you must have quite a nice collection of Chinese books, and if so, it would give me great satisfaction if we could work out a plan by which your collection could also be acquired by the Institute for Advanced Study for this Library...

On 9 May 1946, the Institute sent Princeton University Press a $3,000 publication subsidy for Food and Money in Ancient China. The book was definitely going to happen, though on 14 June 1946 the Press notified the Institute that publication would be delayed until summer 1947. Even that forecast proved to be optimistic.

Guion Moore Gest died in 1948, as did his longtime agent Gillis. In that year, the Institute transferred ownership of the Gest Library to Princeton University. On 7 June 1948, with Food and Money still in its production stages, Robert Oppenheimer, who had become Director of the Institute the previous year, informed Institute faculty member Elias Lowe that Princeton would not keep Swann on as curator after October of that year. That same month, Swann received a paycheck with FINAL stamped on it. She protested that she was entitled to three months' notice. The Institute's Trustees voted an additional two months, but declined to defer her retirement beyond that period. Swann moved to El Paso to live with her sister. She was 67.

In December 1948, Datus Smith of Princeton University Press recommended to Oppenheimer that the Institute grant Swann travel funds, since work on the book was "still dragging on;" the final manuscript had been received only that month. Oppenheimer authorized $300 in January 1949. On 18 March Swann proposed to Oppenheimer another research project, a catalogue of Chinese books, which she said could be completed quite quickly since the responsibility for the operation of the library was no longer hanging over her. This suggestion Oppenheimer declined. Shortly afterward, Swann requested another $500 for travel expenses. No reply from Oppenheimer is extant. The Institute was through with her.

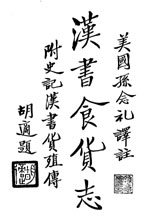

One way or another, the fruit of work done in one place and another, Food and Money did come out in 1950. The eminent Hu Shih had replaced Swann as Curator for the brief period 1950-1952, with the rank of Professor, and the mandate "to find out what was in the collection and what treasures were among them." (He was eventually to report that 41,195 volumes were in a technical sense "rare books") He contributed to her book a formally calligraphed title page, not exactly for the book itself, but for Swann's translation within it:

Princeton said of Food and Money upon its publication:

Miss Swann, who has been Curator of the Gest Oriental Library at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, has succeeded in bringing to her rendition something of the breath of life found in the original: while her translation strives to be literal, at the same time it maintains a remarkable vitality and beauty of its own. Her accompanying articles on Han money, tax terms, Han measurements, a war loan of 154 BC, and the pursuits of wealthy Chinese of the period make original contributions to Sinology and also present some basic material in a new way.

Thus the Sales Department. Their idea of "a new way" consisted at least in part of literary grace. For an adult reader, what is more impressive is the "old way" the book maintains: translation careful (with facsimiles of the original text at the back), notes full and placed at the bottom of the page, index not only present but (at 26 pages) reasonably helpful. Esson M Gale of Michigan, the translator of the Debate on Salt and Iron (1931 and 1934), in a review the following year, took a different line. He stressed the text's "contemporary relativity" (that is, its relevance), and its exhibition of "strikingly modern features in the struggle between bureaucratic and proprietary interests." He ended by allowing that "some minor differences of opinion may be held in the rendition of certain characters" but that

. . . students of Chinese history will do well to acquaint themselves with this revealing study, a major contribution to knowledge of basic Chinese social and economic concepts and practices.

He and Swann were not the only ones to think so. In 1948, after Swann's work was completed but before it was published, there appeared in the Harvard journal Rhea C Blue's article on "The Argumentation of the Shih-huo Chih Chapters of the Han, Wei, and Sui Dynastic Histories." Blue, a Lien-sheng Yang student and CIA operative, gave her address simply as "Washington DC" at the head of her article, which at 118 pages was in effect a Harvard-subsidized monograph.

The Harvard verdict on Swann's work as such was rendered by Yang shortly after its appearance in a December 1950 review article in HJAS. He begins by praising the work as a "major contribution to the understanding of Chinese economic history," "impressive," and "carefully organized," with a "literal and faithful" translation. He then proceeds to show that his student Blue has better understood some of the key terms. Possibly. Little evidence in favor of that possibility, however, is conveyed by Yang's subsequent digression into the economic history of Spring and Autumn times (the infamous "well-field" difficulty), in which, due to a conspicuous lack of preliminary work on the philology and thus the authenticity of the texts in question, neither he nor anybody else at the time knew what they were talking about. Swann had done better to stick to one period, and specifically, a period about whose economic practices and political realities something was independently known.

Duyvendak, in one of the early reviews of Swann's book, felt that

. . . this book is an excellent and careful study in which no pains have been spared to clarify the innumerable knotty problems which the text presents. The author may be proud of what, as I happen to know, has been the labour of many wearisome years.

In considering the treatment of the parallel SJ 129 / HS 91 chapters, included as a separate section of Food and Money and also treated in Rhea Blue's 1948 article, he noted that

Students should do well to consult the two studies together.. . the two studies partly overlap but partly supplement each other. Sometimes they are contradictory . . .

There follow instances where one is right and the other wrong, and one case where both are wrong. Near the end of his review, Duyvendak says the right last thing:

Dr Swann has dedicated her opus magnum to the memory of Mr Guion M Gest, the founder of the Gest Library, now at Princeton, of which, for many years, she was the Curator and where she did her work. This great collection of books found an indefatigable student in its keeper.

So much for the past. The future aspect was perhaps best summed up by Ed Kracke in a 1952 overview of work in Chinese economic history up to and including Swann:

Nancy Lee Swann now gives us the first general study devoted to the economy of the second and first centuries BC. This period is one of special importance for Chinese economic history: It is the earliest time for which a considerable bulk of economic data is available, and we can establish there a bench mark for the surveying of China's economic evolution thereafter. Miss Swann's work is not so much an analytical study of the period she treats, the western Han dynasty, as a critical presentation of the principal source materials relating to the subject, in the form of annotated translations with more detailed studies of certain special phases. Since the sources translated devote over a fifth of their space to Chinese economy from the legendary period down to the end of the third century BC, the book affords valuable materials for the study of China's earlier economic history as well.

With the appearance of Miss Swann's work, the foundation is prepared for an effort to interpret the general nature of western Han economic institutions and the significance of the phenomena they present, from the point of view of the Occidental historian.

Thus, in any case, ended Swann's career as a Sinologist.

The Library went on. Hu Shih was soon succeeded as Gest Library Curator by Hu's assistant James Tung, who served as Curator during 1952-1977. During this period, thanks especially to the foundational efforts of F W Mote (1956) on the Chinese side and Marius Jansen (1959) in Japanese, there was established a substantial Princeton Asian Studies Department. This created a new dynamic, and in 1972 the collection, now known as the Princeton East Asian Library, was moved again, to Palmer and Jones Halls, nearer to the Sinological activity center which it had previously lacked. As subsequently extended under Princeton management, the Gest Library, as it is still sometimes known, ranks as one of the world's more important Chinese libraries. Apart from its rarities, it is third in size in the US, after the slightly larger Harvard-Yenching collection (which it had once outranked), and the Library of Congress holdings, which are almost twice as large.

Swann died in El Paso in 1966. Her Ban Jau book is still in print; a sign equally of our times and of its quality. Her magnum opus, the Food and Money study, is still cited by those fortunate enough to have acquired a copy while doing so was a fiscally feasible procedure. Her epitaph as a library curator was composed by herself, thirty years before her death, in her "Seven Intimate Library Owners" piece. The last paragraph of it reads as follows:

Upon the occasion of the death of Chao Yü, his associate and the instructor of his eldest son, the erudite scholar Ch'üan Tsu-wang, 1705-1755, in a eulogy of him wrote the couplet "Those who have sons do not die; those who compose literature do not decay." Whether or not these seven bibliophiles gained immortality is a question outside the scope of a historical discussion. In and through their libraries, however, they have made an everlasting contribution to the library movement of the Orient, and they and their descendants of the spirit, if not of the flesh, stand ready to allow the western world a share in the riches of the past hidden, at least in part, in the books of China.

E Bruce Brooks

References

- Nancy Lee Swann. Biography of the Empress Teng; A Translation from the Annals of the Later Han Dynasty. JAOS v51 #2 (1931) 138-159

- Nancy Lee Swann. Biography of the Empress Teng; A Translation from the Annals of the Later Han Dynasty. McGill University [Publications Series XXI: Chinese Studies #1] 1931

- Pan Chao: Foremost Woman Scholar of China, First Century AD; Background, Ancestry, Life, and Writings. 1932

- Nancy Lee Swann. A Woman Among the Rich Merchants: The Widow of PA. JAOS v54#2 (1934)

- Rhea C Blue. The Argumentation of the Shih-huo Chih Chapters of the Han, Wei, and Sui Dynastic Histories. HJAS v11 (1948) 1-118

- Nancy Lee Swann. Food and Money in Ancient China; the earliest Economic History of China to AD 25, Han Shu 24 with Related Texts, Han Shu 91 and Shih-chi 129. Princeton 1950

- Joseph Froomkin. [Review of Food and Money in Ancient China]. Journal of Political Economy v58 #5 (1950) 461-462

- J J L Duyvendak. [Review of Food and Money in Ancient China]. T'oung Pao 2ser v40 #1/3 (1950) 210-216

- Yang Lien-sheng. Notes on Nancy Lee Swann's Food and Money in Ancient China. HJAS v13 #3-4 (1950) 524-557

- Esson M Gale. [Review of Food and Money in Ancient China]. AHR v56 #3 (Apr 1951) 577-578

- Lewis Maverick [Review of Food and Money in Ancient China and The Argumentation of the "Shih-huo-chih Chapters of the Han, wei, and Sui Dynastic Histories]. American Economic Review v42 #5 (1952) 626-627

- E A Kracke Jr. The Early Economic History of China. Journal of Economic History v12 #2 (1952) 160-163

- The Association for Asian Studies: A Brief History. JAS v16 #4 (1957) 679-688

Marcia Tucker (Institute for Advanced Study) and Nancy Tomasko (East Asian Library, Princeton University) have contributed to this profile.

9 April 2008 / Contact The Project / Exit to Sinology Page