Homer

Festival CalendarThere is nothing like war to unify a people, there is nothing like devotion to sanctify a marriage, and there is nothing like the weird places of the earth, its caves, its deep seas, to inspire awe and evoke poetry in humankind. Of primitive elements the two Homeric poems seem to have been fashioned. Like the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, the Homeric corpus (and especially its warlike member, the Iliad), functions for its devotees as a sacred grove, an identity focus. It has its pieties, including the conviction that its sole author was "Homer," a person of whom nothing firm is known. It must be added that the Homer cult of earlier years is currently in a bad way. The cultural prestige of ancient Greek texts is no longer what it was in Gladstone's time, when Prime Ministers published volumes on the subject. The Greek language is no longer (or not much longer) beaten bottom-first into every ministerially aspiring British schoolboy. Departments of Classics are vanishing like so many mayflies, and those that remain increasingly lack anything resembling a Homer specialist. We might appropriately give the whole subject a miss, except that it retains a certain technical interest for those who simply want to know what was going on, here and there in antiquity. The Iliad in particular is so obviously the result of an extended formation process that it tempts any historically-minded and text-oriented person. The Odyssey has its quite different charms. Here, then, for those who may happen upon this page, are some names to be aware of, in the long history of Homeric scholarship.

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec

Homer has been identified since antiquity as the author of the Iliad, and less certainly, of the quite different Odyssey. His birthplace is assigned to several of the Ionian islands, perhaps most commonly to Chios, just off the coast of Asia Minor (now Turkey). If we credit him with Iliad 1, we then have, not an Iliad or epic of Troy (the fall of Troy is not even mentioned in the Iliad, thought that tale was known to the author of the Odyssey), but an account of one incident in that story, the Rage (Menis) of Achilles, who being insulted by Agamemnon, refuses to join in the fighting until his sense of honor is satisfied. Much of the material in our Iliad has nothing obvious to do with the working out of that Rage, and some have sought to separate the Menis from these extraneous Books. For present purposes, we will give the name Homer to whoever was responsible for the Menis. As for the date of "Homer," one modern scholarly opinion puts him at somewhere around 0730.

Nausicaa. Samuel Butler (4 December 1835 - 18 January 1902) long ago noted the pervasive tone of feminine sensibility in the Odyssey. "As regards the mind of the writer of the Odyssey, there is nothing that impresses me more profoundly than the undercurrent of melancholy which I feel throughout it. I do not mean that the writer was always, or indeed generally, unhappy; she was often, at any rate,let us hope so, supremely happy; nevertheless there is throughout her work a sense as though the world for all its joyousness was nevertheless out of joint - an inarticulate indefinable half pathos, half baffled fury which even when lost sight of for a time soon re-asserts itself. If the Odyssey was not written without laughter, neither was it written without tears., Now that I know the writer to have been a woman, I am ashamed of myself for not having been guided by the exquisitely subtle sense of weakness as well as of strength that pervades the poem, rather than by the considerations that actually guided me." The Authoress of the Odyssey (to borrow the title of Butler's 1897 book) lived in Trapani, where tourists are still shown the sites of various Odyssean adventures, and where the ship that carried Odysseus home may still be seen in the harbor, frozen into stone by vengeful Poseidon. The Odyssey is manifestly a simpler poem than the Iliad, and whoever wrote it, it makes a good point of entry into the tangled Homeric Problem. The chief Odyssey question is whether this paean to faithful Penelope was not later given a more masculine character by adding the Telemachia (Odyssey 1-4) at the beginning of the poem, and by strengthening Telemachus' role in the slaying of the suitors at its end.

Euripides (05c) either wrote the play Rhesus (as perhaps his earliest work, c0440), or some less known person did, and it came to be attributed to him. It tells of an exploit of Diomedes and Odysseus, secretly entering the Trojan camp by night, killing a newly arrived leader, King Rhesus of Thrace, and stealing his wonderful horses. Euripides' source, if he had one, was surely Iliad 10, the Doloneia, which recounts that same exploit, though with primary focus on the Greeks rather than (as in Euripides' play) on King Rhesus. That the Doloneia episode was not originally part of the Iliad was seen already by the ancient critics. Which has not prevented volumes being written in its defense, in these latter days. One characteristic of the Dioloneia is that it gives us an Exploit (Aristeia) of Odysseus, who elsewhere in the Iliad is distinguished for other qualities (persuasiveness, ingenuity, practicality). It has been thought that this daring Odysseus represents a wish, within late Homeric circles, to bring the Iliadic Odysseus closer to the mighty figure which he cuts at the conclusion of the Odyssey, slaying fifty armed men who have invaded his household, and sought his wife and his position of rulership. That is, to bring the Iliad and the Odyssey closer together in repertoire of the Homeridae, the guild of reciters who had kept them both alive in earlier times.

Hipparchus, the oldest son of the Athenian ruler Pisistratus, instituted the Panathenaea Festival in 0556 (this was before the building of the Acropolis). At the festival, the complete Iliad was performed every four years, with one singer picking up where the previous one had left off. That performance made the Iliad an emblem of Greek military unity, of course under Athenian leadership. Whatever had been its previous condition, the Iliad of the Panathenaea was undoubtedly a fixed and agreed text. It had probably been altered at a few points to increase the prominence of Athens in the story (the Iliad itself implies an origin further north: in Thessaly, the land of Mount Olympus). Whether Hipparchus' Iliad already contained the Doloneia, our Iliad 10, or whether that interruptive episode was later copied from Euripides, is one of the most famous directionality problems in classical literature. The probability is that this story, though certainly extraneous to the Iliad, was added to it in pre-Panathenean times. But there must then have been something of a continuous text for it to be interpolated into. As for Hipparchus, his own tale is not a peaceful one. He succeeded to the leadership of Athens on the death of his father in 0527, but was assassinated by an enemy in 0514.

The Panathenaea made Homer into the teacher of Greece, and Athenian schoolmasters quickly made the Iliad their major textbook. "My father wanted me to be a good man," says someone, "and so . . ."

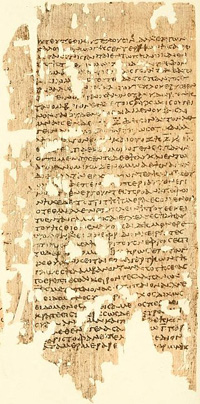

Zenodotus and the other Alexandrian critics sought to stabilize the text of the Iliad, identifying later additions by comparing the manuscripts available to them (such as Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 221, shown here). Some of their excisions seem to have been matters of taste rather than text criticism (like many modern readers, they were offended by the identically repeated lines and tended to remove one of such pairs), but their taste seems to have been pretty sound. Not a few of the lines they marked as doubtful are very plausible as the additions of Athenian schoolmasters, trying to make the connections a little clearer, or expand a bit on some emotion-charged moment. Such material explains "what was already perfectly clear." However it was arrived at, the text of the Iliad established by Aristarchus, the third of the Alexandrians, became standard for centuries thereafter, and relatively little fluctuation o\in the manuscripts occurs thereafter. The point for methodology is that Zenodotus and his successors were aware of the possibility of interpolation in these culturally central texts, sometimes on the largest scale (the Doloneia, with its different Odysseus; the Shield of Achilles, a hymn to peace rather than to war), and were generally sensitive to internal incongruities in the text. This awareness may be said to be the beginning of philological wisdom.

Richard Bentley (27 Jan 1662 - 14 July 1742) had an almost preternatural sense of textual incongruities. He was a contemporary of Newton (they corresponded, and Bentley wrote a popular introduction to Newton's discoveries), and a worthy parallel to Newton: it is with Bentley that the art of philology can be said to have emerged in England. Greatly esteemed in his time were the supposed Epistles of Phalarus, an ancient monarch. Bentley showed that they were full of impossibilities (such as quotes from poets who lived after Phalarus), and that the liberal tone of the Epistles contradicted the evil reputation of Phalarus in classical times. His exposure of the Epistles doomed them within the circle of the learned, though it also earned him the scorn of such as Pope. (Said Bentley of Pope's translation of the Iliad, "It is very pretty poetry, Mr Pope, but you must not call it Homer." Pope retaliated by including Bentley in his Dunciad). Bentley's skill at conjectural emendation (suggesting an alternate reading without support from a variant manuscript) was legendary, and in one instance was confirmed when a manuscript agreeing with his earlier conjecture was discovered. He planned for (and raised a certain amount of money for) a new edition of the New Testament, which would dispense with the Received Text, and be derived anew from the best manuscripts then available. This project did not see fruition, and was realized only later, under Lachmann. As might be expected of a pioneer, Bentley's reach was often further than his grasp, and many of his projects were completed only by others, sometimes with the aid of Bentley's unpublished notes. On the Homeric side, he is credited for detecting the presence of the Digamma, a sound (and letter) present in earlier Greek, and required to make the scansion work, but not represented in our written text of the Iliad. He also saw the primitiveness of the Iliad itself. He wrote in a public letter of 1743, "Take my word for it, poor Homer in those circumstances and early times had never such aspiring thoughts. He wrote a sequel of Songs and Rhapsodies, to be sung by himself for small earnings and good cheer, at Festivals and other days of Merriment; the Ilias he made for the Men, and the Odysseis for the other Sex. These loose Songs were not collected together in the form of an Epic Poem till Pisistratus's time."

Of Bentley's long tenure as Master of Trinity College, Oxford, the less here said the better. Suffice it here to remark that literary acumen does not always translate into administrative tact, and that administrative duties may not be the best imaginable context for literary discovery.

Ossian, Unfortunately for the romantics among us, Ossian never existed. He was the invention of the Scottish poet James MacPherson (27 October 1736 - 17 February 1796) who, riding the current popularity of ancient Gaelic poetry, created Ossian, and composed many things under his name, including the epic poem "Finagle." Not to be found wanting, Scottish authorities presently located Fingal's Cave, a geologically strange formation on the Island of Staffa in the Hebrides, still an officially recognized National Treasure. Cold-eyed contemporaries like Samuel Johnson (himself well acquainted with Scotland and its isles) denounced the Ossian poems as modern inventions. This mattered little in the face of public enthusiasm, including the esteem of Napoleon (Emperor of the French) and Goethe (the national post of Germany). European Romanticism, nurtured from such springs as these, became the New Thing in Europe. Mendelssohn, visiting the area in 1827, wrote a "Hebrides" or "Fingal's Cave" Overture, one of his most inspired creations. Tourism still battens on that enthusiasm, much as Chinese towns bill themselves as possessing the tomb of one or another entirely mythical Ancient Emperor. Truth has its points, but Fiction is what sells. After a successful career in politics, MacPherson himself achieved the ultimate literary distinction of being buried in Westminster Abbey.

The Venetian Scholia. A 10c manuscript of the Iliad, called Venetus A, originally kept in the Biblioteca Marciana Library at Venice (at right, in the above picture of the Piazza San Marco), contained scholia (marginal notes) from which, together with other early manuscripts, Aristarchus' text of the Iliad could be substantially recovered, and the actual thinking of the ancient critics could be directly observed. These "A" scholia were published in 1788 by Jean-Baptiste-Gaspard d'Ansse de Villoison (5 March 1753 - 25 April 1805), and produced a revolution in the understanding of the Iliad text, clearing the way for the modern period of Homeric research. Among the surprises in the scholia was the realization that the ancient critics had often found Homer offensive to their taste, requiring correction and cleanup for the reading public of their time. It was a useful antidote to the established tendency to regard Homer as the sage of antiquity, and the wise teacher of all subsequent humanity. The Conflict between Ancients and Moderns, inspired by the spectacular advances in the natural sciences which were taking place at the time, suggested that Aristotle was not the last word on nature. The corollary was that the previously revered Homer might not be the last word on human nature. Could not a modern poet do better? Such was one current in the thinking of the time.

Friedrich August Wolf (15 Feb 1759 - 8 August 1824), at the age of eighteen, following years of private study, entered the Department of Philology at the University of Göttingen, the catch being that there was then no such department. He studied instead in the University library. After graduation, during his years at Halle (1783-1807) he defined what he meant by philology - "the study of human nature as exhibited in antiquity." This was revolutionary. It brought together all study of antiquity, regardless of the languages in which various ancient texts might have been written. With others, Wolf was excited by the publication of the Venetian Scholia in 1788, and was quick to draw conclusions. His epochal Prolegomena to Homer appeared in 1795, and largely defined the path that Homeric scholarship would take thenceforth. Contemporaries like Heyne had seen the Alexandrians as one more stage in the corruption of the Homeric text. But as Grafton and others noted in the Introduction to their translation of the Prolegomena, "Wolf by contrast wrote the first 'history of a text in antiquity.' He tried to show what the rhapsodes, the diaskeuastai [revisers] and the Alexandrians in turn thought they were doing to and with the original poems. He imagined with as much vividness as his sources permitted what it was like to be a professional reciter in a society passing from orality to literacy; what it was like to be a textual critic in a world without manuals of the ars critica, criteria for assessing the age and independence of manuscripts, and printing presses. Far more than Heyne's lectures - or than any of the other responses to Villoison's edition - the Prolegomena was the history of the Homeric text, at once philological and literary in inspiration, that Villoison had dreamed of helping to create."

One stone of stumbling Wolf left in the path of the future: the conviction that the construction of a long poem requires the use of writing. This ignores what is easily discoverable from modern Inner Asian bardic practice, and the fact that Homer was not a poet, but rather a singer. It drastically underestimates the memory capacity of musicians. Daniel Harris, a professor of voice at mid-century Oberlin, was said to be able, on four hours' notice, to walk onstage and perform any of forty leading operatic roles. This is not verbal memory, it is muscle memory, something that becomes part of the fiber of oneself, while still remaining available for conscious variation whenever occasion may suggest it.

Karl Lachmann (4 March 1793 - 13 March 1851) brought further scientific rigor to textual criticism, the reconstitution of a text from variant manuscripts. He made a mark in three fields: mediaeval German poetry, including such figures as Walter von der Vogelweide (1827); New Testament (his edition of 1831, revised in 1842 and 1850, carried out Bentley's unfulfilled plan of editing the text anew from the best available manuscripts), and Classics (his 1850 edition of Lucretius was a widely admired masterpiece). He has been much criticized by a perhaps envious posterity, but as Wilamowitz said, at the end of a rather caustic account, in his history of philology, "Where would we be without Lachmann?" Lachmann's notes on Homer's Iliad appeared in 1837 and 1841, and with support from his work on the Nibelungenlied and other sagas, posited that the poem originally had the form of eighteen separate lays. Neither his eighteen, nor the sixteen of Koechly (1861), nor any of several other attempts along this line has proved convincing. But the basic idea, that the gigantic final Iliad was not improvised in a day, but rested on a tradition of more modest performance pieces, appears to be sound. One more step in the direction already marked out by Bentley.

Adolf Kirchhoff (6 January 1826 - 20 February 1908), a Berliner whose professional life was spent as Professor of Classical Philology at the University of Berlin, was a student of inscriptions (he edited one section of the Corpus Inscriptionum Atticarum), and of Greek tragedy (he produced the first critical edition of Euripides in 1855, and later edited Aeschylus (1880), as well as Hesiod's Works and Days (1881). He was a statesman of the field, and edited the journal Hermes from 1866 to 1881. For his notable services, he was elected an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1888. Still later came his study of the sources of Thucydides (1895). But his major monument is Die Homerische Odyssee (1859), in which for the first time the unitary view of that text, including the originality of the first four Books, the Telemachia, was challenged in detail. His work, like that of his older contemporary Lachmann, marks a major advance. It sees the Odyssey not as a poem, but as the end product of a formation process. One feature of Kirchhoff's analysis was to doubt the originality of the Telemachia (Books 1-4), and of other features of the text that tended to emphasize the importance of Telemachus in the story.

Walter Leaf (26 November 1852 - 8 March 1927), in addition to his work on the Iliad, had a distinguished career as a banker; he served as president of both the International Chamber of Commerce and the Classical Association. He was regarded as the leading Homerist of his day. His edition of the Iliad (1886-1888) was long considered standard, as was his translation, done with Andrew Lang and Ernest Myers (1892, 1911). His theories of the formation of the Iliad are conveniently set forth in his Companion to the Iliad for English Readers (1892). He considered that the Menis (the Rage of Achilleus) was the oldest part of the poem, and the only part due to Homer, everything else being later additions. Leaf went very far in stripping the Iliad of anything not directly relevant to the Menis, the rage of Achilles. He considered that the Greek Wall was a later addition, that Patroclus' body was not recovered, nor had Patroclus been wearing Achilleus' armor, hence there was no need for the Shield of Achilles passage. Nor was there, originally, an Embassy to Achilles (Iliad 9). For Leaf, the Menis comprised Books 1, part of 2, 11, part of 15, 16, and 22.

William D Geddes (21 November 1828 - 9 February 1900) was born in Aberdeen, and from 1860 was a Professor (from 1885, Principal) at the University of Aberdeen. He did much to raise the standard of the teaching of Greek in Scotland, both at schools and at the early Scottish universities. His 1855 Greek Grammar was in its 17th edition by 1883 (revised edition 1893). On the textual level, his edition of Plato's Phaedo (1885) was highly esteemed. He also published much on Celtic lore and tradition, and was knighted in 1892. In 1878 appeared the closely argued Problem of the Homeric Poems, in which he largely followed the view of George Grote (17 November 1794 - 18 June 1871), whose History of Greece began to appear in 1846, that the Iliad consisted of an original core (which Geddes called the Achlleid), plus later additions. Geddes introduced the idea that the additions represented influence from the Odyssey; he called these the "Ulyssean" portions of the Iliad. For Geddes, the original Iliad comprised Books 1, 8, and 11-22.

Many observations in both these books retain their usefulness, and are recommended for current study. Leaf's caution (Companion 28f) remains not only valid, but urgently so: "It must not be supposed then that because we say that a certain passage is "late," or is "an addition," or even an "interpolation," it is therefore inferior . . . . In fact, among the parts of the Iliad which are always recognised as the latest, we find as a rule most of the passages of noble pathos which sink deepest into our hearts." But what is fatal to both these models of the Iliad is the conviction that its earliest stratum is by "Homer." Evidence in the text, and economic considerations, alike suggest that "Homer" is the author of the Menis (the Rage of Achilles), the "monumental composer" of recent theory; and that his work rests on, and in its way culminates, a long previous bardic tradition of shorter performance modules.

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (22 December 1848 - 25 September 1931), a lifelong rival of the philosopher Nietzsche, who for him represented a departure from sound philological principles; his chief statement was a reply to Nietzsche, The Philology of the Future (1872-1873). He was an indefatigable reader, and once greeted a young student who had come to visit him by bounding down the stairs, early in the morning, and asking, "What are you reading?" The center of his work was the Homeric corpus, with Title appearing in 0000, and Title in 0000l. He there presents an extremely complex picture of the formation process for both texts, so complex as to be self-defeating for many readers. Which is not to say that is too complex to be true, and unwary would be the later researcher who publishes on a line of Homer without checking to see what Wilamowitz thought of it. It must be added that in addition to his philological acumen, Wilamowitz was not immune to the attractions of mere literary beauty. George M Bolling (13 April 1871 - 1 June 1963) remarked of this susceptibility, at Iliad 10:240, "That Wilamowitz likes the line is a matter of taste, with which its interpolator would agree."

Friedrich Nietzsche (15 October 1844 - 25 August 1900) went through the same schooling as Wilamowitz (the famous Schulpforta, then the University of Bonn), but four years earlier. Where Wilamowitz was inspired by Otto Jahn, Nietzsche was the protégé of Ritschl, who secured for him a professorship at Basel at the early age of 24. The two were temperamentally antithetical, but their argument about what philology was or should be did have its point. Where mainline Altertumswissenschaft looked to utility in the present world, and regarded Greek culture as the acme of rationality and beauty, and thus the ideal teacher of modern persons and societies, Nietzsche emphasized instead what he called the Dionysian elements in ancient Greece, its irrational and dangerous aspect. He was much influenced by the Eastern thought currents drifting through Europe at this time (as was Schopenhauer), and especially attracted by the idea of "eternal return." He was an early enthusiast for the music of Wagner, with its basis in pagan myth. In terms of method, he emphasized the differentness of the past.

Tempo. Not all advances in scholarship come from scholars. The Homeric poems are not poems, they are performance pieces, and we also need to hear from musicians. In December 1905, a live presentation of part of Iliad 17 was given at the Berlin Opera House "Unter den Linden." It turned out that the rate of delivery on that occasion was about 6 seconds per hexameter line; that is, one syllable per standard heartbeat. Subsequent testing by the present writer (with the cooperation of several living Homerists) has confirmed that, though singers can go faster, this heartbeat tempo is near to the rate of maximum audience intelligibility. The Homeric poems were for long the property of a guild of reciters (the "Homeridae" of legend), and it may be assumed that, as with the centuries-long performance tradition of the Biblical Psalms, not only diction, but tempo, remained more or less constant over time. Then to get the approximate performance time for any part of the Iliad or the Odyssey, however far back that part may be thought to go, we simply divide the line count by 10 to get the time in minutes. Iliad Book 1, which with small exceptions seems to be more or less intact as first composed, and which in our text consists of 611 lines, would then represent a performance session of 61 minutes: about an hour. A majority of our present Iliad Books will fit something like that module. The ten Books which time out at substantially over an hour (2, 5, 9, 11, 13, 15-17, and 23-24), seem to have a different social expectation, and may require special attention.

Denys Page (11 May 1908 - 6 July 1978), a student of Gilbert Murray at Christ Church, Oxford, where he had a distinguished undergraduate career, winning every prize in sight in 1928, and a First in Literae Humaniores in 1930. He studied for a year in Vienna under Ludwig Rademacher (his knowledge of German would soon prove very useful), and then returned to Oxford; his book Actors' Interpolations in Greek Tragedy appeared in 1934. He was appointed a Junior Censor at Oxford in 1937. Tense times ensued. Page married Katherine Dohan (daughter of Bryn Mawr graduate and noted Mycenaean archaeologist Edith Hall Dohan) in Rome in 1939. Later that year, war broke out, and Page was assigned to the Bletchley Park codebreaking operation, becoming head of section ISOS ("Illicit Signals") under Oliver Strachey, and a member of the XX ("Double Cross," or Disinformation) Committee in 1942; Page succeeded Strachey as Director when Strachey retired in 1944. At war's end, Page headed a special mission to Lord Mountbatten's headquarters, first at Kandy (Ceylon) and later in Singapore. He returned to Oxford in 1946. Not long after, in 1950, he became Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge He served as Master of Jesus College, Cambridge, from 1959 on, and was knighted in 1971. In that same year, he became President of the British Academy (he had been a Fellow since 1952), a position he held until his retirement in 1974.

To the Homeric poems, Page brought not only a codebreaker's sense, of what was out of place, or shall we say, disinformational, but a devastating wit. He took on the Odyssey in his 1954 Flexner Lectures at Bryn Mawr. "My audience included such connoisseurs of Homeric poetry as Rhys Carpenter and Richmond Lattimore: I must make it very clear from the start that I was addressing myself not to them, but to their students." For those students, Page made wicked fun of the absurdities in the present text. He also showed how they might have arisen. He realized that the Odyssey, though not as long as the Iliad, was equally unperformable as a whole, and was instead a repertoire of possible performances. In the performance of one module, a reciter might add framing material - either totally irrelevant, or borrowed from the wrong place elsewhere in the poem - to explain things to the audience. Page is under no illusion that Book 1 is an afterthought, but sees that it effectively introduces what follows; it is in the joins of the Telemachia to the rest of the material that trouble arises. The lectures were published as The Homeric Odyssey in 1955 (that book's use of word statistics to suggest the different authorship of the Iliad and the Odyssey was ridiculed by in a 1959 review by unitarian Douglas Young of North Carolina, based on a supposed parallel investigation into word use in early and late Milton). A slightly different service for the Iliad was rendered in his Sather Lectures at Berkeley in October and November of 1957, published as History and the Homeric Iliad in 1959. Noted Frederick Combellack of the University of Oregon at the beginning of one review, "In the year when these lectures were being delivered in Berkeley, the rumor spread along the Coast that each lecture had to be scheduled in a larger room than the previous one, since each room proved inadequate for the audience. All those who had ever heard Page lecture found this story easy to believe; all who read this book will feel that the story ought to be true, whether it is so in fact or not." In addition to six chapters surveying the archaeological and other evidence for the Iliad's relation to things Mycenaean, the book contains an appendix: two chapters on traditional philological problems: the Embassy to Achilles (which, with Leaf, he thinks never occurred), and the Building of the Greek Wall (where he tackles much-discussed assumption of Thucydides 1/10:5ff, that it was built, not in the tenth year, as the Iliad requires us to assume, but in the first; Again with Leaf, he concludes that the wall is a later addition to the story). The forty-year-old Geoffrey Kirk concluded his 1961 review by saying, "The reviewer has read this brilliant book several times, each time with profit and keen interest. He predicts that very many others will do the same, and that it will achieve a permanent place in the annals of Homeric scholarship." But other reviewers, he noticed the anomaly of the last two chapters, and said of the Wall solution, "But the argument that this and consequential passages must therefore be post-Thucydidean in composition will not find much favour." We are not there yet.

Geoffrey Kirk (3 December 1921 - 10 March 2003). Ulysses S Grant wrote his memoirs, entirely omitting his two terms as President of his country (during which time, among other things, he established the system for international arbitration of maritime disputes), and mentioned only his service in the earlier Civil war. Noted Homerist Geoffrey Kirk also wrote a memoir, which dealt solely with his service during World War 2, where he and others in disguised and heavily armed local schooners sailed up and down the Cyclades Islands, off the east coast of Greece, and as far as the coast of Turkey (ancient Ionia), landing assault parties, attacking Germans, and rescuing partisans. His service in the ranks of Homerists nevertheless deserves a word or two. In that second service, like Grant, he reached the top. He took his degree after returning from the war, in 1946, was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1959 (Vice-President, 1972-1973), and reached the pinnacle, the Regius Professorship of Greek at Cambridge, in 1974, retiring in 1982. His first work was on the Greek philosophers, Heraclitus (1954) and the Presocratics (1957). He then turned to Homer, with The Songs of Homer (1962, revised as Homer and the Epic, 1965); an edited collection, Language and Background of Homer (1964); several studies on myth (1970, 1974); and Homer and the Oral Tradition (1976). His 1962 view of the Iliad was complicated by the need to address recent "oralist" approaches (A B Lord was one of the readers of his manuscript), and the Mycenaean world recently revealed by the Linear B decipherment (John Chadwick was another reader). He wound up, in 1962, with a gradually accumulating Iliad, in which, for example, . . .

Whatever one's personal sense of the Iliad and its formation process, the thousands of students want a simple view, and the hundreds of scholars want a commentary in which every line of the text is addressed, never mind whether it is early or late in the text's history, or whether it displays, or obscures, the original poet's conscious design. Hence the rather rueful note prefacing the first volume (1986) of the six-volume Iliad commentary which Kirk oversaw as the first fruits of his retirement, and to which he contributed the parts on Iliad 1-8. It reads, "The author may be thought to be adopting in this volume a somewhat more "unitarian" approach to the Iliad than he has in earlier writing. That reflects, perhaps, a small change in his own position, but primarily it is because, other things being equal and for one who is hoping to produce helpful and objective comments, it is better to err on the side of conservatism, of treating the text as a reasonable reflection of Homer's own poem." We are not there yet, and we are somewhat slipping back.

Martin West (23 September 1937 - 13 July 2015) took a wide, and also a deep, view of Greek tradition. He explored its Asiatic components in Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient (1971; translated into Italian in 1993), and again in The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth (1997), which noted parallels in Biblical and Babylonian texts. Old Testament parallels to Homer and Hesiod had been pointed out long before by Zachary Bogan (1658), but this had left no mark on Homeric scholarship. "In those days, of course, it was common enough for Latin, Greek, and Hebrew to be studied in parallel. From the late eighteenth century, Classical studies became more isolationist. Works such as Bogan's were forgotten, or at any rate left unopened; I do not know whether anyone but myself has read him in the last two hundred years." An important source of information abort epic is early lyric, and West's study of Greek Lyric Poetry appeared in 1993. Unlike many Classicists, he recognized the importance of performance in early Greek poetry, and wrote a study of Ancient Greek Music in 1994. Said he in the Introduction, "Ancient Greek culture was permeated with music. Probably no other people in history has made more frequent reference to music and musical activity in its literature and art. Yet the subject is practically ignored by nearly all who study that culture or teach about it." He returned to the subject in 2001, with Documents of Ancient Greek Music: The Extant Melodies and Fragments (with Egert Pohlmann). His edition of Homer (Homeri Ilias) was published by Teubner in 1998 and 2000, followed by Studies in the Text and Transmission of the Iliad (De Gruyter, 2001). Translations of the Homeric Hymns and Greek Epic Fragments (both Loeb) appeared in 2003. Two overviews followed, The Making of the Iliad in 2011 and The Making of the Odyssey in 2014. The latter was not altogether complimentary: "The poet of the Odyssey was a seriously flawed genius. He had a wonderfully inventive imagination, a gift for pictorial detail and for introducing naturalistic elements into epic dialogue, and a grand architectural plan for the poem. He was also a slapdash artist, often copying verses from the Iliad or from himself without close attention to their suitability . . . " The matter of common lines in the Odyssey, and between it and the Iliad; indeed, the whole subject of what are sometimes called "formulas," remains a matter for further investigation. West's edited text of the Odyssey, the capstone of his work on the basic Homeric corpus, appeared posthumously from De Gruyter in 2017.

Stephanie West was Lecturer in Classics at Hertford College (Oxford) from 1966 to 2005, and from 1981 to 2005 also at Keble College (Oxford); she was elected as a Fellow of the British Academy in 1990 (the photo above is the one posted at the Academy). She met Martin at a lecture by Eduard Fraenkel in 1960. Martin's first trip to Greece was in that same year; He had memorized one of two surviving Delphic Paean melodies, and "on arriving at Delphi I sang it at the top of my voice in the ruins of the sanctuary where it had had its premiere 2,084 springs previously My two traveling companions distanced themselves somewhat. A little later, as we examined the stone on which the text is inscribed, one of the stumbled against it, and it nearly crashed from its moorings and shattered. (I married her all the same)." Theirs was that rare thing in academe: a collaborative marriage. Each publicly acknowledged the assistance of the other. Said Stephanie at the end of the Prefatory Note to her commentary on Odyssey 1-4, "But my greatest debt is to my husband, Martin, whose patience, learning, and lucidity have repeatedly extricated me from difficulty." She had replaced the unexpectedly deceased unitarian Douglas Young (1913-1973) in the Odyssey commentary of Alfred Heubeck and others (6v in Italian, 1981; 3v English translation, 1988, 1989, 1992). Hers, as it happened, was the responsibility for Books 1-4, the controversial Telemachia. The group leader, Heubeck, was a firm believer in the unitary authorship of the Odyssey, and thus of the originality of the Telemachia, with all the questions it raises about the prominence of Telemachus in the story. Stephanie duly notes that the Telemachia is essential to the Odyssey as we have it. But on p51, she registers this dissent: "The prominent part which [Telemachus] plays in our Odyssey leaves Penelope little more than an onlooker, though vestiges remain of an earlier version in which she was Odysseus' accomplice in exacting vengeance from the suitors."

The vestiges do indeed remain. Who, together with Odysseus, plotted the death of the suitors? That question is before the court. We may call to witness the dead suitors themselves, who ought to know. Here is their testimony, as it stands in Odyssey 24:125-129, 167-172 (Lattimore's version):

We were courting the wife of Odysseus, who had been long gone.

She would not refuse the hateful marriage, nor would she bring it

about, but she was planning death and black destruction

with this other stratagem of her heart's devising:

She set up a great loom in her palace, and set to weaving . . .Then in the craftiness of his mind, [Odysseus] urged his lady

to set the bow and the gray iron in front of the suitors,

the contest for us ill-fated men, the start of our slaughter.

Not one of us was able to hook the string on the powerful

bow, but all of us were found far too weak for it.But when the great bow was given into the hands of Odysseus . . .

And with that return to its beginning, our survey may suitably end. Perhaps in time to come, someone or ones may be moved to take up this unfinished task.