|

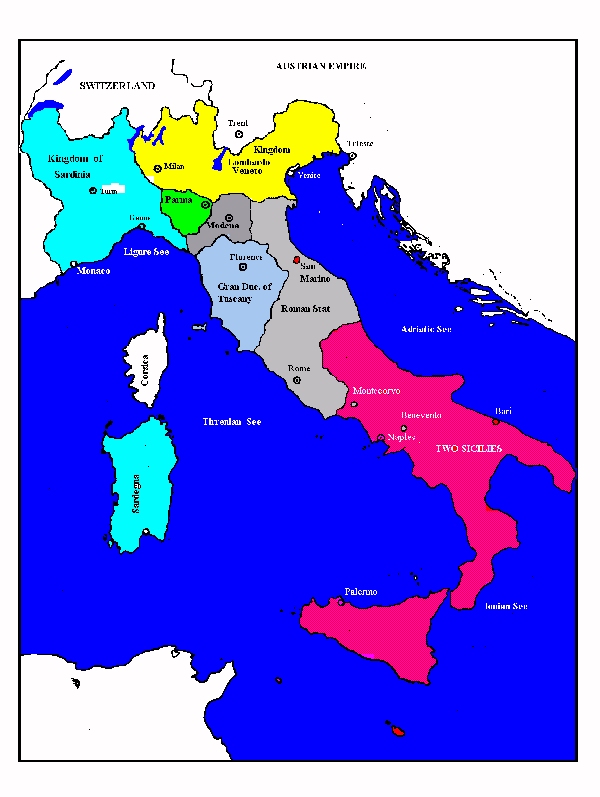

| Italy Map 1 | |

|

| Italy: Unification

[For an alternate depiction of the Renaissance North Italian states, see Map 2]. For comparison, here are the divisions of Italy just before the unification of the modern state of Italy. It too is divided into three zones, with a Rome-dominated group in the middle. Roughly southern Italy is poor, and northern Italy plus the central "Terza Italia" (Emiligia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria, the Marche, plus Veneto, Friuli, and Trentino in the northeast) is prosperous.

The nature and origin of these differences is a theme explored in Francis Fukuyama, Trust (1995), 97f. He finds that the lack of lateral institutions in the south, the high level of "social distrust," and the overly atomistic nature of family structures, is a legacy of "the Norman kingdoms in Sicily and Naples, particularly under Frederick II. The southern kingdoms established an early form of monarchical absolutism, snuffing out the independence of towns that displayed a desire for autonomy" and creating an enduring species of monarchical absolutism and centralized authority. The lack of intermediate institutions, or the social habits out of which they could be innovated, leads in southern Italy as in Russia to the emergence of quasi-families, the Mafia and its analogues, which provide an artificially enforced substitute. "In a society where the bonds of trust outside the family are weak, the blook oaths taken by members of La Cosa Nostra serve as surrogate kinship bonds that allow criminals to trust one another in situations in which betrayal is very tempting" (101). One is reminded of the code of the grave robbers, an inversion and caricature of Chinese social trust values, in Jwangdz 10:1c, in which the spokesman is in fact the most notorious robber of the age.

All lectures and abstracts posted on this site are Copyright © by their authors. 19 Apr 2002 / Contact The Project / Conferences Page |